The Early Days of Gold Mining and Its Price Impact

Gold mining has a history stretching back thousands of years, with its earliest records dating to ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Yet, it wasn’t until the 19th century that industrialized gold mining began reshaping both economies and market dynamics. The California Gold Rush of 1848-1855 and subsequent discoveries in Australia and South Africa dramatically increased global gold production. These booms had clear impacts on gold prices, though not always in ways one might expect. During gold rushes, the sudden surge in available gold initially depressed prices locally due to oversupply. However, because gold was a monetary standard in much of the world, the increased production often contributed to broader monetary expansion rather than a permanent price collapse. Historical data from this period shows gold’s purchasing power remained relatively stable through the 19th century even as mining output expanded. It wasn’t a simple matter of more gold equaling lower prices—global economic growth often absorbed increased supply. Thus, early history teaches that the relationship between mining output and gold prices is complex, dependent on broader monetary systems, economic conditions, and demand factors rather than simple supply metrics alone.

The 20th Century: Technological Advances and New Discoveries

The 20th century saw profound changes in mining technology that greatly boosted gold production. The introduction of cyanide extraction techniques, mechanized drilling, and large-scale open-pit mining enabled producers to access lower-grade ores profitably. Key discoveries, such as South Africa’s Witwatersrand Basin, contributed heavily to global supply. Between 1900 and 1980, gold production rose steadily, yet prices remained largely tethered to the fixed-rate systems like the Gold Standard and later the Bretton Woods system. Only after the U.S. abandoned the gold standard in 1971 did gold prices become fully market-driven. In the post-Bretton Woods era, production data and price began interacting more dynamically. Gold production accelerated during the 1980s and 1990s, but so did demand for gold as an investment and jewelry asset, cushioning price impacts. However, large discoveries became rarer toward the late 20th century. Experts began noting “peak gold”—the idea that the most accessible and richest gold deposits had already been found. As ore grades declined and costs rose, maintaining output required far greater investment, signaling potential future supply constraints. This structural change planted seeds for the supply-driven price rallies of the early 21st century.

The Early 2000s: A New Mining Boom Amid Surging Demand

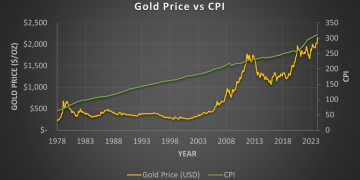

Entering the 21st century, gold enjoyed a major bull run fueled by a mix of factors: declining real interest rates, heightened geopolitical risks, and emerging market wealth. Between 2000 and 2010, gold prices quadrupled. The mining industry responded as expected—exploration budgets ballooned, and new projects were fast-tracked. Major producers expanded aggressively into new regions, from West Africa to Central Asia. Mining supply rose modestly but lagged the surge in prices. Many of the new projects faced challenges: political instability, environmental protests, rising production costs, and technical difficulties. Data from the World Gold Council shows that while mining output increased by about 24% between 2000 and 2018, it was nowhere near enough to create a supply glut. Instead, gold’s price strength persisted. The early 2000s experience emphasized an important modern reality: the long lead times and complexities of gold mining mean that supply is relatively inelastic in the short-to-medium term. Even when prices soar, it can take years for new mines to come online and for production to respond meaningfully. Meanwhile, growing investor and central bank demand kept pushing prices higher, demonstrating that modern gold price dynamics are driven more by demand than supply.

Recent Trends: Is Gold Supply Peaking?

In the past decade, gold production trends have started flashing warning signals. According to the U.S. Geological Survey and other industry reports, global gold output peaked around 2018-2019 and has plateaued or slightly declined since. Major producers like China, Australia, Russia, and South Africa are reporting lower ore grades and rising production costs. Environmental regulations are tightening, community opposition is mounting, and political risk in key mining regions is escalating. As a result, even maintaining current output levels is proving challenging. New gold discoveries have also plummeted. S&P Global Market Intelligence notes that major new gold deposits have become exceedingly rare, with exploration success rates declining sharply over the past two decades. In short, the world is digging deeper, moving more earth, and spending more money to get less gold. This constrained supply environment suggests that unless technological breakthroughs or significant new discoveries occur, the mining industry may struggle to materially increase output. This scenario is fundamentally bullish for long-term gold prices, assuming demand remains stable or rises.

Market Expectations: How Supply Trends Shape Future Price Dynamics

The market is increasingly factoring in the tight supply outlook. Analysts note that in an environment where mining output cannot keep pace with potential demand drivers—such as inflation concerns, central bank buying, and safe-haven flows—gold prices are likely to trend higher over time. Importantly, current mining supply constraints could magnify price volatility. When gold demand spikes during crises, a flexible supply could traditionally cushion price surges. With today’s constrained supply, however, price spikes could be sharper and more dramatic. Conversely, if demand weakens—say, due to a surge in real interest rates or prolonged periods of economic strength—gold could still face price corrections. Yet even in downturns, tight supply may provide a higher floor for prices than in previous eras when production could flood the market. Institutional investors, including pension funds and central banks, are increasingly mindful of these dynamics. Reports show growing strategic allocations to gold, not just as an inflation hedge but as a finite resource asset facing long-term scarcity issues. This “scarcity premium” concept could become an important new pillar of gold’s investment case over the next decade.

Conclusion

The history of gold mining and its relationship with price dynamics offers a fascinating window into the complex forces that govern one of the world’s most treasured commodities. From the heady days of the California Gold Rush to the industrial boom of the 20th century, and now into an era of tightening supply constraints, the gold market has continually evolved. Historical mining data reveals that supply surges have rarely led to permanent price collapses; rather, demand growth has often absorbed increased output. Today’s market presents a new challenge: global gold supply is peaking, production costs are rising, and major discoveries are dwindling. These realities point to a future where gold’s scarcity will likely enhance its investment appeal. Investors would do well to monitor mining trends closely, as they offer crucial insights into the long-term trajectory of gold prices. As with many natural resources, the story of gold in the coming decades may increasingly be one of scarcity, resilience, and renewed value.