Gold has long been regarded as a symbol of wealth, power, and stability. For millennia, it has served as a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a hedge against both inflation and uncertainty. Yet, beyond its cultural and historical significance, gold is also an asset class with a measurable investment track record. By examining gold’s historical return rates, patterns of price corrections, and performance over various economic cycles, investors can gain a clearer picture of how to approach gold strategically within their portfolios. A historical perspective not only demystifies the metal’s long-term behavior but also illuminates practical lessons for future investment decisions.

Gold’s Long-Term Return Profile

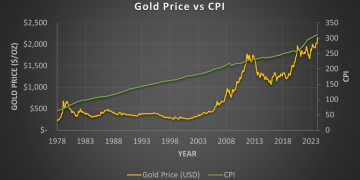

Unlike equities or bonds, gold is a non-yielding asset. It does not generate interest or dividends, making its performance entirely reliant on capital appreciation. Yet, when measured over long time horizons, gold has demonstrated a surprisingly resilient return profile. According to historical data from the World Gold Council and other financial institutions, gold has provided an average annual return of approximately 7–8% over the past 50 years. This return is competitive with other major asset classes and particularly impressive when accounting for its lower correlation with traditional markets.

For instance, from 1971—when the U.S. officially ended the gold standard—to 2021, gold prices surged from $35 per ounce to over $1,800. This growth equates to an average annual return of roughly 8%, during which the metal weathered multiple recessions, inflationary spikes, and global crises. Notably, during the 2000s and early 2010s, gold experienced a strong bull market, rising from under $300 to a peak of $1,900 per ounce in 2011, largely driven by global financial instability and loose monetary policy.

However, gold’s performance is not always upward. Investors must understand that its return profile is often uneven and cyclical, with extended periods of sideways movement or declines. This highlights the importance of timing and strategy when incorporating gold into an investment portfolio.

Understanding Past Price Corrections

Gold’s price history includes notable corrections and long drawdown periods. These moments are critical learning opportunities for investors. For example, after peaking in 1980 at around $850 per ounce amid double-digit inflation and geopolitical tension, gold entered a prolonged bear market. Over the next two decades, it fell steadily, bottoming out near $250 in 1999. This nearly 70% decline in nominal terms—and even more in inflation-adjusted terms—illustrates the risk of entering gold at the top of a speculative bubble.

Another correction occurred after gold’s 2011 high. Following a decade-long rally, the metal dropped to below $1,050 by late 2015, as fears of inflation waned, interest rates began to rise, and investor appetite shifted back to equities. This correction served as a reminder that gold’s value often responds inversely to real interest rates and investor sentiment about monetary policy and economic stability.

Despite these corrections, gold’s long-term trend has been upward. The key takeaway is that gold, like any asset, is subject to cycles. Price corrections often follow exuberant rallies, but patient investors who view these as opportunities rather than failures tend to benefit in the long run. Gold tends to reassert its value when macroeconomic or geopolitical risks re-emerge, making it a valuable counter-cyclical asset.

Lessons from Historical Performance Cycles

Gold’s investment history can be divided into several performance cycles, each offering distinct lessons. The 1970s, for example, were marked by high inflation, the oil embargo, and the collapse of the Bretton Woods system. Gold soared during this time, as investors sought refuge from eroding fiat currency values. This cycle teaches the importance of gold during inflationary upheaval and monetary uncertainty.

Conversely, the 1980s and 1990s were decades of declining inflation, rising interest rates, and robust equity market returns. Gold underperformed, trading sideways or downward. This cycle highlights gold’s vulnerability during periods of economic optimism and high real yields.

The 2000s brought renewed interest in gold as debt-fueled growth, geopolitical instability, and fears of currency devaluation prompted investors to reallocate toward safe-haven assets. The 2008 global financial crisis reinforced this trend, with gold climbing sharply as central banks implemented aggressive monetary easing. This era showcases gold’s effectiveness as a crisis hedge and inflation anticipator.

Understanding these cycles allows investors to frame gold’s role more accurately. It is not a growth stock and should not be treated as such. Instead, gold performs best in environments of risk aversion, monetary expansion, and currency weakness. Aligning gold exposure with these macro trends can enhance portfolio resilience and returns.

Strategic Allocation and Long-Term Investment

Historical data underscores the effectiveness of gold as a strategic component of a diversified investment portfolio. Studies by the World Gold Council have shown that including gold in a balanced asset allocation can reduce portfolio volatility and improve risk-adjusted returns, particularly during economic downturns.

For long-term investors, gold is best viewed as an insurance policy against extreme events—economic collapses, banking crises, inflation shocks, or geopolitical unrest. Allocating between 5% and 15% of a portfolio to gold can provide stability during equity market declines and currency fluctuations.

Dollar-cost averaging is another strategy supported by historical behavior. Since gold can be volatile in the short term, regular incremental purchases help smooth out the impact of market timing and avoid overexposure during price spikes.

Physical gold, ETFs, mining stocks, and futures all offer different levels of exposure, risk, and liquidity. Each comes with its own cost structure and market behavior. Historical returns vary slightly between these vehicles, but all generally follow the broader trends of spot gold pricing.

Using History to Anticipate Future Behavior

While no investment strategy guarantees success, history offers a reliable guide to understanding potential outcomes. Gold’s consistent revaluation during periods of crisis provides a compelling case for its inclusion in future-oriented strategies.

For example, with global debt levels at historic highs, central banks still maintaining dovish policies, and ongoing geopolitical tensions, gold could be poised for another significant role in the years ahead. Climate-driven disruptions, political instability, or a resurgence of inflation could reignite demand for the yellow metal.

Furthermore, as digital assets and central bank digital currencies emerge, the role of traditional stores of value like gold may evolve, but not diminish. Investors who learn from gold’s past will be better positioned to capitalize on its future potential.

Conclusion: History as a Compass for Gold Investors

Gold’s historical returns provide a roadmap for today’s investors. While not without volatility, gold has proven its value as a long-term asset, particularly during periods of macroeconomic instability. Past price corrections offer critical lessons about patience, timing, and strategic allocation. By examining performance across different economic cycles, investors can appreciate gold’s role not only as a safe haven but also as a disciplined investment.

Incorporating gold based on historical patterns enhances portfolio diversification and offers a buffer against the unknown. As the global economy continues to face new challenges, the enduring lessons of gold’s past will remain vital in guiding intelligent investment decisions.